Technical Deep Dive: Stirling Numbers and the Antoniak Distribution

JoonHo Lee

2026-01-01

Source:vignettes/theory-stirling.Rmd

theory-stirling.RmdOverview

This vignette provides a deep technical treatment of the computational machinery underlying the Antoniak distribution—the exact probability mass function (PMF) for the number of distinct clusters in a Dirichlet Process (DP) model. We focus specifically on unsigned Stirling numbers of the first kind and their numerically stable computation, which forms the core of the DPprior package’s reference computational layer.

This vignette is intended for statisticians and methodological researchers who want to understand the exact implementation details. We cover:

- The combinatorial definition and properties of unsigned Stirling numbers

- The computational challenge: why naive implementation fails

- Log-space computation via the

logsumexptrick - Computing the Antoniak PMF from Stirling numbers

- Numerical stability analysis and implementation guards

Throughout, we distinguish between established results from the combinatorics and Bayesian nonparametrics literature and implementation contributions of this package.

1. Unsigned Stirling Numbers of the First Kind

1.1 Definition and Combinatorial Interpretation

The unsigned Stirling numbers of the first kind, denoted , count the number of permutations of elements that consist of exactly disjoint cycles.

Example. For elements , the permutations grouped by number of cycles are:

| Permutations | Count | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| 2 | 3 | |

| 3 | 1 |

The total is , as expected since we’re partitioning all permutations.

Attribution. Stirling numbers have a rich history in combinatorics, dating back to James Stirling’s 1730 work Methodus Differentialis. The connection to the DP cluster distribution was established by Antoniak (1974).

1.2 Recurrence Relation

The unsigned Stirling numbers satisfy a fundamental recurrence:

Combinatorial interpretation: When adding element to a permutation of elements :

- Element can form a new cycle by itself: this accounts for permutations (we need cycles in the first elements)

- Element can be inserted into any position within an existing cycle: there are positions to insert, and we need cycles already present, giving

1.4 Fundamental Identity

A crucial identity that serves as a computational verification is:

This follows immediately from the fact that we’re partitioning all permutations according to their cycle count.

# Compute log-Stirling numbers up to J = 15

logS <- compute_log_stirling(15)

# Verify known values

cat("Verification of known Stirling numbers:\n")

#> Verification of known Stirling numbers:

cat(sprintf(" |s(4, 2)| = %d (expected: 11)\n", round(exp(logS[5, 3]))))

#> |s(4, 2)| = 11 (expected: 11)

cat(sprintf(" |s(5, 3)| = %d (expected: 35)\n", round(exp(logS[6, 4]))))

#> |s(5, 3)| = 35 (expected: 35)

cat(sprintf(" |s(6, 3)| = %d (expected: 225)\n", round(exp(logS[7, 4]))))

#> |s(6, 3)| = 225 (expected: 225)

cat(sprintf(" |s(10, 5)| = %d (expected: 269325)\n", round(exp(logS[11, 6]))))

#> |s(10, 5)| = 269325 (expected: 269325)

# Verify row sum = J!

J_test <- 10

log_row_sum <- logsumexp_vec(logS[J_test + 1, 2:(J_test + 1)])

log_factorial <- sum(log(1:J_test))

cat(sprintf("\nRow sum identity for J = %d:\n", J_test))

#>

#> Row sum identity for J = 10:

cat(sprintf(" sum_k |s(%d,k)| = %.0f\n", J_test, exp(log_row_sum)))

#> sum_k |s(10,k)| = 3628800

cat(sprintf(" %d! = %.0f\n", J_test, exp(log_factorial)))

#> 10! = 3628800

cat(sprintf(" Relative error: %.2e\n", abs(exp(log_row_sum - log_factorial) - 1)))

#> Relative error: 0.00e+002. The Computational Challenge

2.1 Explosive Growth of Stirling Numbers

The unsigned Stirling numbers grow extremely rapidly—faster than exponential. Consider some representative values:

| J | |s(J, 1)| | |s(J, ⌊J/2⌋)| | log₁₀(max |s(J,k)|) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 3.6288e+05 | 2.69325e+05 | 5.56 |

| 20 | 1.2200e+17 | 1.40000e+13 | 17.09 |

| 50 | 6.0800e+62 | 1.05000e+52 | 62.78 |

| 100 | 9.3300e+156 | 3.70000e+130 | 156.97 |

| 200 | NA | NA | 373.02 |

For , the maximum Stirling number is approximately , far exceeding the range of double-precision floating point ( maximum, but with only 15-17 significant digits).

The key insight: Direct computation in the original scale is impossible for any practical . We must work entirely in log-space.

2.2 Why Naive Log-Space Fails

One might think: “Just take logs of everything!” But consider the recurrence:

In log-space, this becomes:

where . The problem: we need to compute where and may be very large (causing overflow when exponentiating) or very different in magnitude (causing underflow when adding).

3. The logsumexp Trick

3.1 Mathematical Foundation

The logsumexp function computes

in a numerically stable way using the identity:

Why this works:

- The maximum is factored out, so we never exponentiate a large number

- The argument to is always , preventing overflow

- We use

log1p(x)= for numerical stability near

3.2 Implementation and Verification

# Demonstrate numerical stability

cat("logsumexp numerical stability:\n")

#> logsumexp numerical stability:

# Case 1: Both arguments very large

a <- 1000

b <- 1000

result <- logsumexp(a, b)

expected <- 1000 + log(2) # log(e^1000 + e^1000) = 1000 + log(2)

cat(sprintf(" logsumexp(1000, 1000) = %.6f (expected: %.6f)\n", result, expected))

#> logsumexp(1000, 1000) = 1000.693147 (expected: 1000.693147)

# Case 2: Both arguments very negative

a <- -1000

b <- -1000

result <- logsumexp(a, b)

expected <- -1000 + log(2)

cat(sprintf(" logsumexp(-1000, -1000) = %.6f (expected: %.6f)\n", result, expected))

#> logsumexp(-1000, -1000) = -999.306853 (expected: -999.306853)

# Case 3: Large difference in magnitude

a <- 1000

b <- -1000

result <- logsumexp(a, b)

cat(sprintf(" logsumexp(1000, -1000) = %.6f (essentially 1000)\n", result))

#> logsumexp(1000, -1000) = 1000.000000 (essentially 1000)

# Case 4: Typical use case - log-sum of probabilities

log_p1 <- log(0.3)

log_p2 <- log(0.7)

result <- exp(logsumexp(log_p1, log_p2))

cat(sprintf(" exp(logsumexp(log(0.3), log(0.7))) = %.6f\n", result))

#> exp(logsumexp(log(0.3), log(0.7))) = 1.0000003.3 Vectorized Version

For computing , we use the vectorized extension:

# Demonstrate vectorized logsumexp

x <- c(100, 101, 102, 103)

result <- logsumexp_vec(x)

cat(sprintf("logsumexp_vec([100, 101, 102, 103]) = %.4f\n", result))

#> logsumexp_vec([100, 101, 102, 103]) = 103.4402

cat(sprintf("This equals: log(e^100 + e^101 + e^102 + e^103) ≈ log(e^103 * 1.52) = %.4f\n",

103 + log(1 + exp(-1) + exp(-2) + exp(-3))))

#> This equals: log(e^100 + e^101 + e^102 + e^103) ≈ log(e^103 * 1.52) = 103.44024. Computing the Log-Stirling Matrix

4.1 The Algorithm

The compute_log_stirling() function builds the complete

lower-triangular matrix of log-Stirling numbers using the recursion:

Complexity: time and space.

# Compute the full log-Stirling matrix for J up to 50

J_max <- 50

logS <- compute_log_stirling(J_max)

cat(sprintf("Log-Stirling matrix dimensions: %d x %d\n", nrow(logS), ncol(logS)))

#> Log-Stirling matrix dimensions: 51 x 51

cat(sprintf("Memory usage: %.2f KB\n", object.size(logS) / 1024))

#> Memory usage: 20.53 KB

# Display a small section of the matrix (J = 1 to 10)

cat("\nlog|s(J, k)| for J = 1..10, k = 1..10:\n")

#>

#> log|s(J, k)| for J = 1..10, k = 1..10:

small_section <- round(logS[2:11, 2:11], 2)

rownames(small_section) <- paste("J =", 1:10)

colnames(small_section) <- paste("k =", 1:10)

print(small_section)

#> k = 1 k = 2 k = 3 k = 4 k = 5 k = 6 k = 7 k = 8 k = 9 k = 10

#> J = 1 0.00 -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf

#> J = 2 0.00 0.00 -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf

#> J = 3 0.69 1.10 0.00 -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf

#> J = 4 1.79 2.40 1.79 0.00 -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf

#> J = 5 3.18 3.91 3.56 2.30 0.00 -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf

#> J = 6 4.79 5.61 5.42 4.44 2.71 0.00 -Inf -Inf -Inf -Inf

#> J = 7 6.58 7.48 7.39 6.60 5.16 3.04 0.00 -Inf -Inf -Inf

#> J = 8 8.53 9.48 9.48 8.82 7.58 5.77 3.33 0.00 -Inf -Inf

#> J = 9 10.60 11.60 11.68 11.12 10.02 8.42 6.30 3.58 0.00 -Inf

#> J = 10 12.80 13.84 13.97 13.49 12.50 11.06 9.15 6.77 3.81 04.2 Verification via Row Sums

We can verify the computation by checking that row sums equal :

# Verify row sum identity for multiple J values

cat("Verification of sum_k |s(J,k)| = J!:\n")

#> Verification of sum_k |s(J,k)| = J!:

cat(sprintf("%5s %15s %15s %12s\n", "J", "sum |s(J,k)|", "J!", "Rel. Error"))

#> J sum |s(J,k)| J! Rel. Error

cat(strrep("-", 48), "\n")

#> ------------------------------------------------

for (J in c(5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50)) {

log_row_sum <- logsumexp_vec(logS[J + 1, 2:(J + 1)])

log_factorial <- sum(log(1:J))

rel_error <- abs(exp(log_row_sum - log_factorial) - 1)

# Display in scientific notation for large values

cat(sprintf("%5d %15.4e %15.4e %12.2e\n",

J, exp(log_row_sum), exp(log_factorial), rel_error))

}

#> 5 1.2000e+02 1.2000e+02 0.00e+00

#> 10 3.6288e+06 3.6288e+06 0.00e+00

#> 20 2.4329e+18 2.4329e+18 7.11e-15

#> 30 2.6525e+32 2.6525e+32 1.42e-14

#> 40 8.1592e+47 8.1592e+47 1.42e-14

#> 50 3.0414e+64 3.0414e+64 2.84e-145. The Antoniak Distribution

5.1 Exact PMF of

The fundamental result connecting Stirling numbers to the DP cluster distribution is the Antoniak distribution (Antoniak, 1974):

where is the rising factorial (Pochhammer symbol).

Attribution. This formula was derived by Antoniak (1974) and is foundational to the Bayesian nonparametrics literature. It is restated in modern DP prior-elicitation work including Dorazio (2009), Murugiah and Sweeting (2012), and Vicentini and Jermyn (2025). Zito, Rigon, and Dunson (2024) present the general Gibbs-type form .

5.2 Log-Space Computation

In log-space, the PMF becomes:

where .

Normalization: The PMF is computed in log-space and then converted to probabilities via the softmax function, which ensures:

- Numerical stability for extreme parameter values

- Exact normalization to sum to 1

# Compute the Antoniak PMF for J = 50, alpha = 2

J <- 50

alpha <- 2

pmf <- pmf_K_given_alpha(J, alpha, logS)

# Verify normalization

cat(sprintf("PMF normalization check: sum(pmf) = %.10f\n", sum(pmf)))

#> PMF normalization check: sum(pmf) = 1.0000000000

# Summary statistics

k_vals <- 0:J

mean_K <- sum(k_vals * pmf)

var_K <- sum(k_vals^2 * pmf) - mean_K^2

mode_K <- which.max(pmf) - 1

cat(sprintf("\nDistribution of K_%d | α = %g:\n", J, alpha))

#>

#> Distribution of K_50 | α = 2:

cat(sprintf(" E[K] = %.4f\n", mean_K))

#> E[K] = 7.0376

cat(sprintf(" Var(K) = %.4f\n", var_K))

#> Var(K) = 4.5356

cat(sprintf(" Mode(K) = %d\n", mode_K))

#> Mode(K) = 7

cat(sprintf(" SD(K) = %.4f\n", sqrt(var_K)))

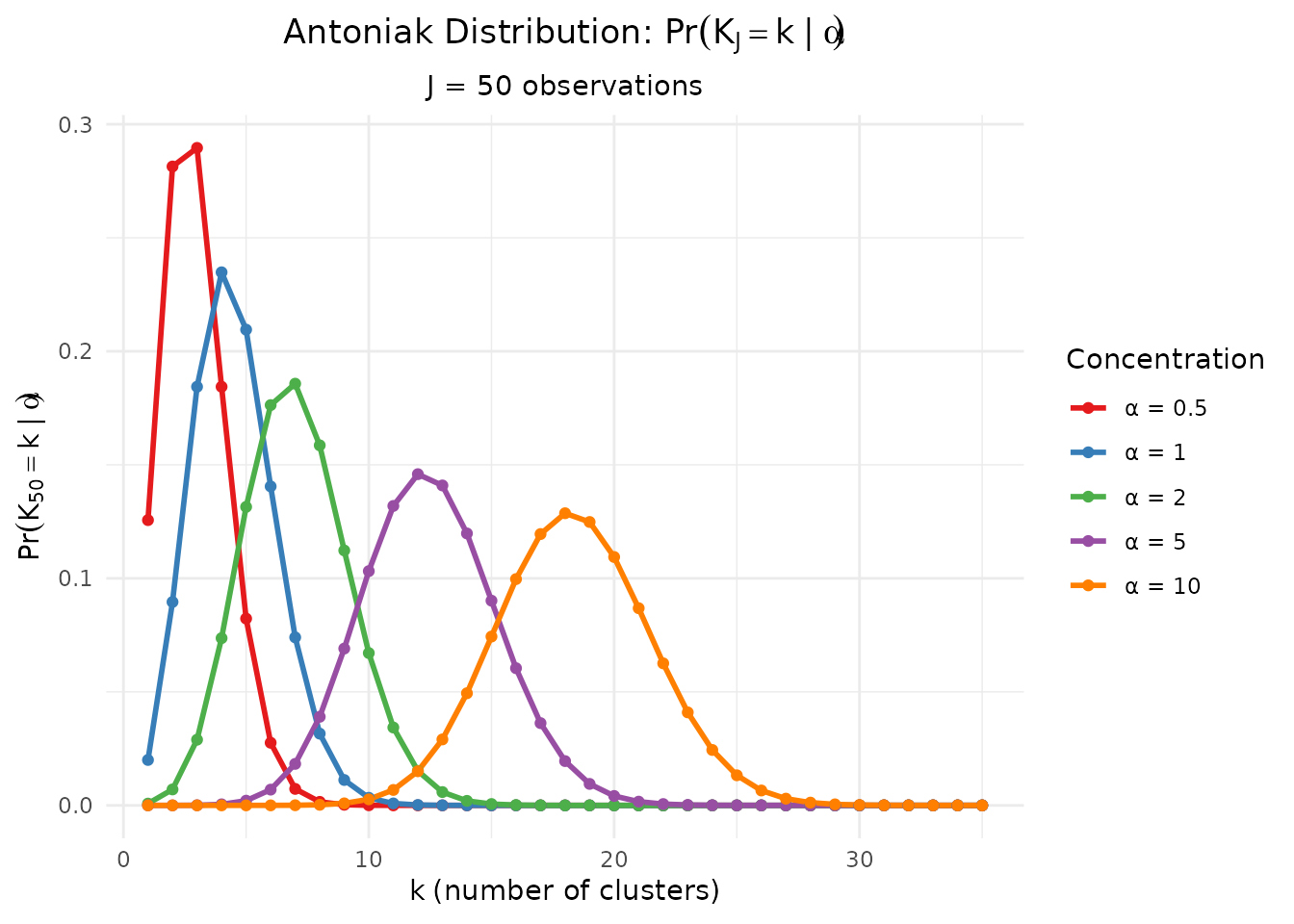

#> SD(K) = 2.12975.3 Visualization

# Compute PMF for several alpha values

alpha_values <- c(0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10)

J <- 50

pmf_data <- do.call(rbind, lapply(alpha_values, function(a) {

pmf <- pmf_K_given_alpha(J, a, logS)

k_range <- 1:min(35, J)

data.frame(

k = k_range,

pmf = pmf[k_range + 1],

alpha = factor(paste0("α = ", a))

)

}))

ggplot(pmf_data, aes(x = k, y = pmf, color = alpha)) +

geom_line(linewidth = 1) +

geom_point(size = 1.5) +

scale_color_manual(values = c("#E41A1C", "#377EB8", "#4DAF4A", "#984EA3", "#FF7F00")) +

labs(

x = expression(k ~ "(number of clusters)"),

y = expression(Pr(K[50] == k ~ "|" ~ alpha)),

title = expression("Antoniak Distribution: " * Pr(K[J] == k ~ "|" ~ alpha)),

subtitle = "J = 50 observations",

color = "Concentration"

) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(

legend.position = "right",

plot.title = element_text(face = "bold", hjust = 0.5),

plot.subtitle = element_text(hjust = 0.5)

)

Antoniak PMF for various concentration parameters α with J = 50 observations.

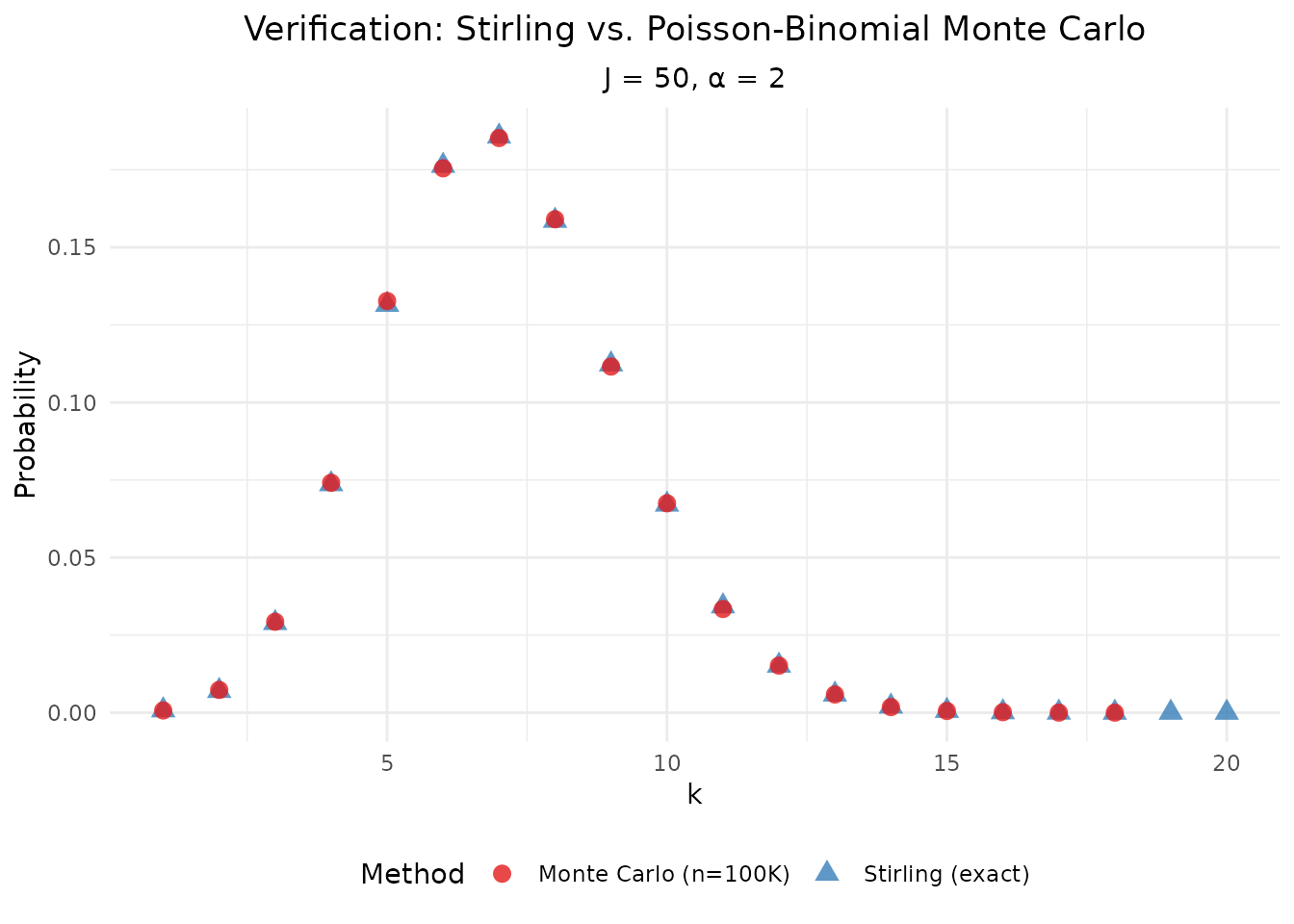

5.4 Comparison with the Poisson-Binomial Representation

The Antoniak distribution can be alternatively derived from the

Poisson-binomial representation (Theorem 1 in

theory-overview):

This provides an independent verification of our Stirling-based computation:

# Monte Carlo simulation using Poisson-Binomial representation

n_sim <- 100000

J <- 50

alpha <- 2

# Bernoulli success probabilities

p <- alpha / (alpha + (1:J) - 1)

# Simulate K_J

set.seed(123)

K_samples <- replicate(n_sim, sum(runif(J) < p))

# Compare distributions

k_range <- 1:20

pmf_stirling <- pmf_K_given_alpha(J, alpha, logS)[k_range + 1]

pmf_mc <- tabulate(K_samples, nbins = max(K_samples))[k_range] / n_sim

comparison_df <- data.frame(

k = rep(k_range, 2),

pmf = c(pmf_stirling, pmf_mc),

Method = rep(c("Stirling (exact)", "Monte Carlo (n=100K)"), each = length(k_range))

)

ggplot(comparison_df, aes(x = k, y = pmf, color = Method, shape = Method)) +

geom_point(size = 3, alpha = 0.8) +

scale_color_manual(values = c("#E41A1C", "#377EB8")) +

scale_shape_manual(values = c(16, 17)) +

labs(

x = expression(k),

y = "Probability",

title = expression("Verification: Stirling vs. Poisson-Binomial Monte Carlo"),

subtitle = sprintf("J = %d, α = %g", J, alpha)

) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(

legend.position = "bottom",

plot.title = element_text(face = "bold", hjust = 0.5),

plot.subtitle = element_text(hjust = 0.5)

)

#> Warning: Removed 2 rows containing missing values or values outside the scale range

#> (`geom_point()`).

Verification: Stirling-based PMF vs. Monte Carlo from the Poisson-Binomial representation.

6. Numerical Stability Analysis

6.1 Critical Regions

The Antoniak PMF computation faces numerical challenges in extreme parameter regions:

Very small (< 0.1): The distribution becomes highly concentrated at , with as . This requires careful handling of probabilities very close to 1.

Very large (> 50): The distribution shifts toward , and the log-probabilities for small become extremely negative.

# Examine behavior at extreme alpha values

J <- 50

extreme_alphas <- c(0.01, 0.1, 1, 10, 50, 100)

cat("PMF stability at extreme α values (J = 50):\n")

#> PMF stability at extreme α values (J = 50):

cat(sprintf("%8s %12s %12s %12s %12s\n",

"α", "Pr(K=1)", "E[K]", "Mode(K)", "sum(pmf)"))

#> α Pr(K=1) E[K] Mode(K) sum(pmf)

cat(strrep("-", 60), "\n")

#> ------------------------------------------------------------

for (a in extreme_alphas) {

pmf <- pmf_K_given_alpha(J, a, logS)

k_vals <- 0:J

mean_K <- sum(k_vals * pmf)

mode_K <- which.max(pmf) - 1

sum_pmf <- sum(pmf)

cat(sprintf("%8.2f %12.6f %12.2f %12d %12.10f\n",

a, pmf[2], mean_K, mode_K, sum_pmf))

}

#> 0.01 0.956274 1.04 1 1.0000000000

#> 0.10 0.643925 1.43 1 1.0000000000

#> 1.00 0.020000 4.50 4 1.0000000000

#> 10.00 0.000000 18.34 18 1.0000000000

#> 50.00 0.000000 34.91 35 1.0000000000

#> 100.00 0.000000 40.71 41 1.00000000006.2 Implementation Guards in DPprior

The DPprior package includes several defensive measures:

Log-space computation throughout: All intermediate calculations remain in log-space until the final softmax

Stable softmax: Uses the shifted exponential trick to prevent overflow:

Input validation: The

assert_positive()andassert_valid_J()helpers catch invalid inputs earlyDefensive renormalization: Final PMF vectors are explicitly normalized to sum to 1

6.3 Digamma Function Stability

The conditional moments of involve the digamma function:

For very small , , which can cause numerical issues. The package uses threshold-based switching to alternative formulations when needed:

# Compare digamma-based moments with PMF-based computation

J <- 50

alpha_test <- c(0.01, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10)

cat("Moment computation consistency check:\n")

#> Moment computation consistency check:

cat(sprintf("%8s %12s %12s %12s\n",

"α", "E[K] (ψ)", "E[K] (PMF)", "Rel. Diff"))

#> α E[K] (ψ) E[K] (PMF) Rel. Diff

cat(strrep("-", 48), "\n")

#> ------------------------------------------------

for (a in alpha_test) {

# Digamma-based computation

mean_digamma <- mean_K_given_alpha(J, a)

# PMF-based computation

pmf <- pmf_K_given_alpha(J, a, logS)

mean_pmf <- sum((0:J) * pmf)

rel_diff <- abs(mean_digamma - mean_pmf) / mean_pmf

cat(sprintf("%8.2f %12.6f %12.6f %12.2e\n",

a, mean_digamma, mean_pmf, rel_diff))

}

#> 0.01 1.044631 1.044631 8.50e-16

#> 0.10 1.432776 1.432776 1.08e-15

#> 0.50 2.937775 2.937775 2.12e-15

#> 1.00 4.499205 4.499205 1.38e-15

#> 2.00 7.037626 7.037626 2.90e-15

#> 5.00 12.460485 12.460485 2.14e-15

#> 10.00 18.342355 18.342355 2.13e-157. Computational Performance

7.1 Pre-computation Strategy

For typical use in prior elicitation (where is fixed for a given analysis), the log-Stirling matrix should be computed once and cached:

# Timing for log-Stirling matrix computation

J_values <- c(50, 100, 200, 300, 500)

cat("Log-Stirling matrix computation times:\n")

#> Log-Stirling matrix computation times:

cat(sprintf("%8s %15s %15s\n", "J_max", "Time (ms)", "Memory (KB)"))

#> J_max Time (ms) Memory (KB)

cat(strrep("-", 40), "\n")

#> ----------------------------------------

for (J_max in J_values) {

time_taken <- system.time({

logS_temp <- compute_log_stirling(J_max)

})["elapsed"] * 1000

mem_kb <- object.size(logS_temp) / 1024

cat(sprintf("%8d %15.2f %15.1f\n", J_max, time_taken, mem_kb))

}

#> 50 9.00 20.5

#> 100 39.00 79.9

#> 200 165.00 315.8

#> 300 363.00 708.0

#> 500 1000.00 1961.27.2 PMF Computation Timing

Once the Stirling matrix is cached, PMF computation is extremely fast:

# Pre-compute Stirling matrix

logS_300 <- compute_log_stirling(300)

# Time PMF computation for various J

cat("\nPMF computation times (with pre-computed Stirling matrix):\n")

#>

#> PMF computation times (with pre-computed Stirling matrix):

cat(sprintf("%8s %8s %15s\n", "J", "α", "Time (μs)"))

#> J α Time (μs)

cat(strrep("-", 35), "\n")

#> -----------------------------------

for (J in c(50, 100, 200, 300)) {

for (alpha in c(1, 5)) {

time_us <- mean(replicate(100, {

t <- system.time(pmf_K_given_alpha(J, alpha, logS_300))["elapsed"]

})) * 1e6

cat(sprintf("%8d %8.1f %15.1f\n", J, alpha, time_us))

}

}

#> 50 1.0 80.0

#> 50 5.0 30.0

#> 100 1.0 40.0

#> 100 5.0 160.0

#> 200 1.0 140.0

#> 200 5.0 130.0

#> 300 1.0 130.0

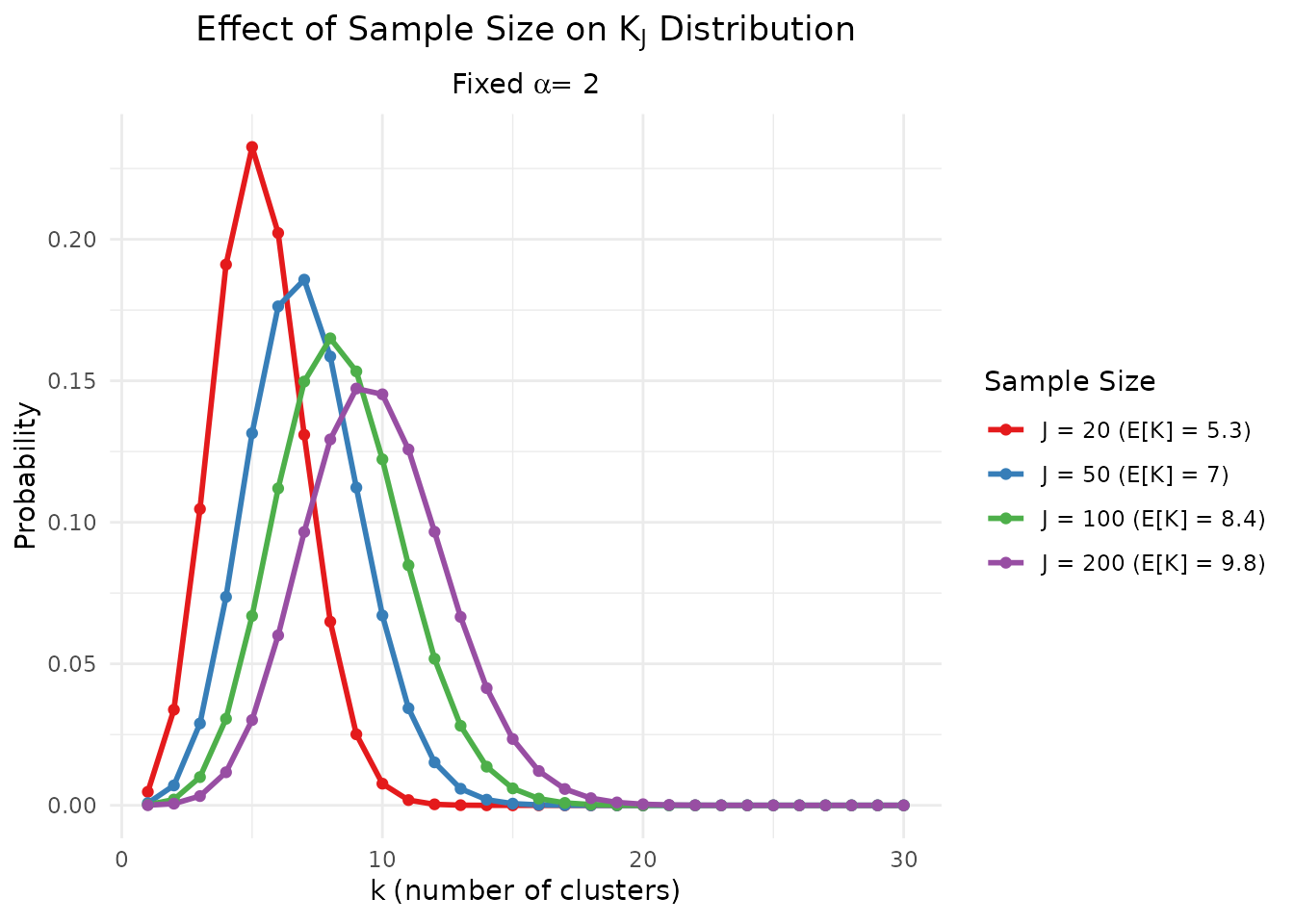

#> 300 5.0 110.08. Application: Effect of J on the Distribution

Understanding how the distribution of changes with sample size is crucial for prior elicitation. For fixed :

# Effect of J on K distribution

alpha <- 2

J_values <- c(20, 50, 100, 200)

logS_200 <- compute_log_stirling(200)

# Compute PMFs for different J

effect_data <- do.call(rbind, lapply(J_values, function(J) {

pmf <- pmf_K_given_alpha(J, alpha, logS_200)

k_max <- min(30, J)

mean_K <- sum((0:J) * pmf)

data.frame(

k = 1:k_max,

pmf = pmf[2:(k_max + 1)],

J = factor(paste0("J = ", J, " (E[K] = ", round(mean_K, 1), ")"))

)

}))

ggplot(effect_data, aes(x = k, y = pmf, color = J)) +

geom_line(linewidth = 1) +

geom_point(size = 1.5) +

scale_color_manual(values = palette_main) +

labs(

x = expression(k ~ "(number of clusters)"),

y = "Probability",

title = expression("Effect of Sample Size on " * K[J] * " Distribution"),

subtitle = expression("Fixed " * alpha * " = 2"),

color = "Sample Size"

) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(

legend.position = "right",

plot.title = element_text(face = "bold", hjust = 0.5),

plot.subtitle = element_text(hjust = 0.5)

)

Effect of sample size J on the distribution of K for fixed α = 2.

Summary

This vignette has provided a detailed treatment of the computational machinery underlying the Antoniak distribution:

Unsigned Stirling numbers count permutations with exactly cycles and satisfy a well-defined recurrence relation.

Numerical challenge: Direct computation overflows for ; we must work entirely in log-space.

The

logsumexptrick enables stable computation of for any values of and .The Antoniak distribution provides the exact PMF of via Stirling numbers, computed stably in log-space.

DPprior implementation: Pre-computes and caches the log-Stirling matrix, enabling fast PMF evaluation for any .

The stable computation of the Antoniak PMF forms the foundation for the package’s exact moment-matching algorithms (A2) described in subsequent vignettes.

References

Antoniak, C. E. (1974). Mixtures of Dirichlet processes with applications to Bayesian nonparametric problems. The Annals of Statistics, 2(6), 1152-1174.

Arratia, R., Barbour, A. D., & Tavaré, S. (2003). Logarithmic Combinatorial Structures: A Probabilistic Approach. European Mathematical Society.

Dorazio, R. M. (2009). On selecting a prior for the precision parameter of Dirichlet process mixture models. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference, 139(10), 3384-3390.

Murugiah, S., & Sweeting, T. J. (2012). Selecting the precision parameter prior in Dirichlet process mixture models. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference, 142(7), 1947-1959.

Vicentini, C., & Jermyn, I. H. (2025). Prior selection for the precision parameter of Dirichlet process mixtures. arXiv:2502.00864.

Zito, A., Rigon, T., & Dunson, D. B. (2024). Bayesian nonparametric modeling of latent partitions via Stirling-gamma priors. arXiv:2306.02360.

Appendix: Key Function Reference

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

compute_log_stirling(J_max) |

Pre-compute log-Stirling matrix for |

get_log_stirling(J, k, logS) |

Safe accessor with bounds checking |

validate_stirling(logS) |

Verify against known reference values |

verify_stirling_row_sum(logS) |

Verify identity |

logsumexp(a, b) |

Numerically stable |

logsumexp_vec(x) |

Vectorized log-sum-exp |

softmax(x) |

Numerically stable softmax |

pmf_K_given_alpha(J, α, logS) |

Antoniak PMF for |

log_pmf_K_given_alpha(J, α, logS) |

Log-scale Antoniak PMF |

For questions about this vignette or the DPprior package, please visit the GitHub repository.