Exact Moment Matching: The A2 Newton Algorithm

JoonHo Lee

2026-01-01

Source:vignettes/theory-newton.Rmd

theory-newton.RmdOverview

This vignette provides a rigorous mathematical treatment of the

A2 Newton algorithm (A2-MN) used in the DPprior package

to achieve exact moment matching for Gamma hyperprior elicitation. While

the A1 closed-form approximation (see

vignette("theory-approximations")) provides a fast

initialization, it introduces systematic errors that can be substantial

for small-to-moderate

—precisely

the regime most relevant for multisite trials and meta-analyses in

education.

We cover:

- The problem formulation: moment matching as root-finding

- The Jacobian: score-based derivation (avoiding finite differences)

- Convergence analysis: local quadratic convergence

- Numerical safeguards: damping, positivity constraints, and fallback strategies

- A1 vs. A2 comparison: quantifying the improvement

Throughout, we carefully distinguish between established results from the numerical analysis literature and novel contributions of this work in applying these methods to DP hyperprior calibration.

1. Problem Formulation

1.1 The Inverse Problem

Recall from vignette("theory-overview") that we seek

Gamma hyperparameters

such that the induced marginal distribution of

under

has user-specified moments:

The A1 approximation solves this problem under a Negative Binomial proxy, yielding closed-form expressions that are asymptotically exact as . However, for finite , the A1 solution may not satisfy the exact moment equations.

Goal of A2. Find

such that the exact marginal moments, computed via

Gauss-Laguerre quadrature (see

vignette("theory-overview")), match the targets precisely:

1.2 Newton-Raphson Iteration

Attribution. Newton’s method for systems of nonlinear equations is a classical algorithm in numerical analysis; see Ortega & Rheinboldt (1970) for the theoretical foundations.

Novel Contribution. This work applies Newton’s method to the specific problem of DP concentration prior calibration, with (i) exact Jacobian computation via score identities, (ii) A1 as a principled initializer, and (iii) a complete set of numerical safeguards for robust convergence.

Given the current iterate , the Newton update is: where is the Jacobian matrix:

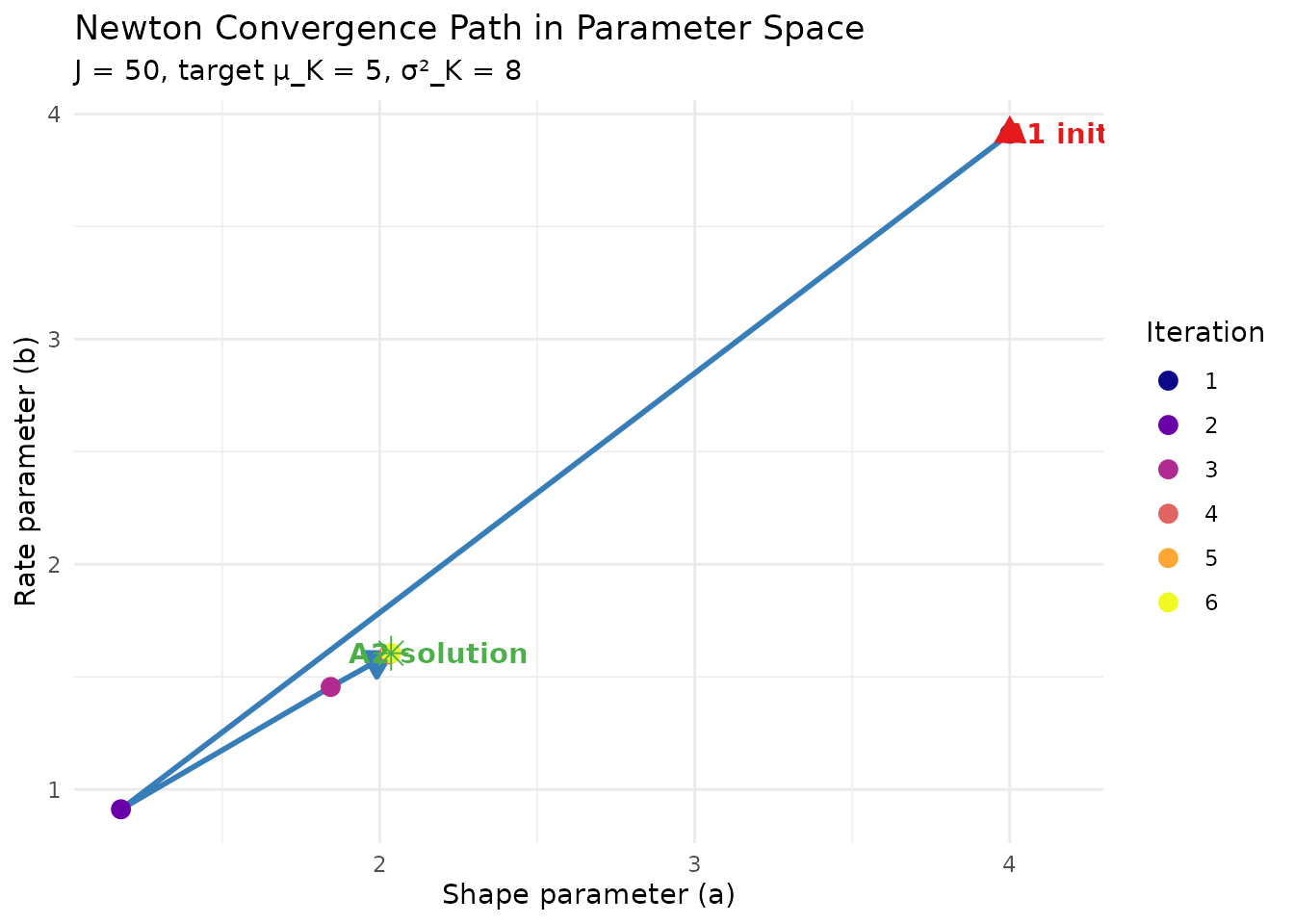

Schematic of Newton’s method converging to the root of F(a,b) = 0.

2. The Jacobian: Score-Based Derivation

2.1 Score Function Identities

Attribution. The use of score functions for computing derivatives of expectations is a standard technique in statistical theory; see Casella & Berger (2002, Chapter 7). The key identity is: where is the score function.

Novel Contribution. This work applies these identities specifically to the moment functions, enabling exact Jacobian computation without finite differences.

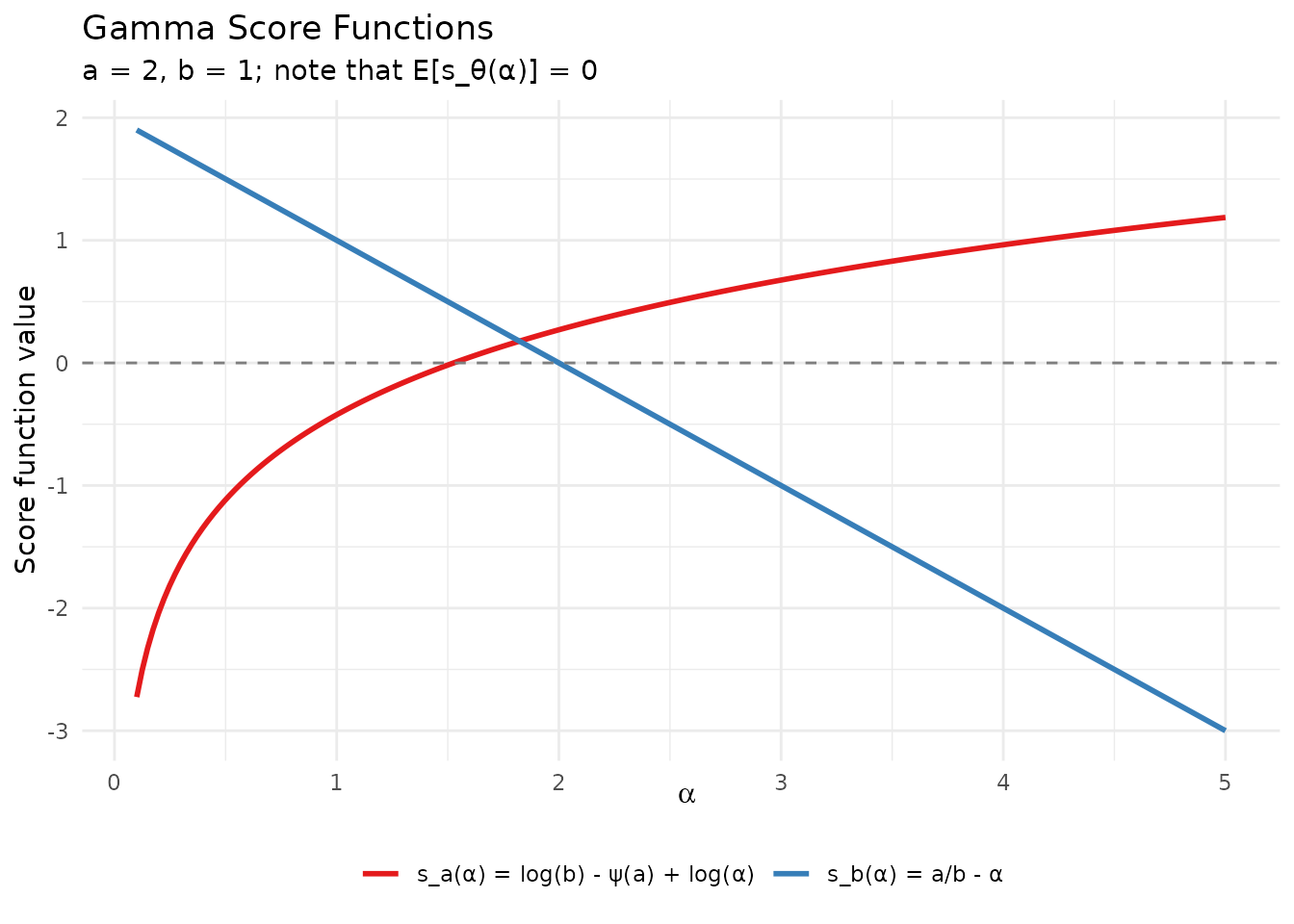

For the Gamma distribution (shape , rate ), the score functions are: where denotes the digamma function.

A fundamental property is that , which serves as a numerical verification check.

# Visualize score functions

a <- 2

b <- 1

alpha_grid <- seq(0.1, 5, length.out = 200)

score_df <- data.frame(

alpha = rep(alpha_grid, 2),

score = c(

score_a(alpha_grid, a, b),

score_b(alpha_grid, a, b)

),

Type = rep(c("s_a(α) = log(b) - ψ(a) + log(α)",

"s_b(α) = a/b - α"), each = length(alpha_grid))

)

ggplot(score_df, aes(x = alpha, y = score, color = Type)) +

geom_line(linewidth = 1) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, linetype = "dashed", color = "gray50") +

scale_color_manual(values = palette_main[1:2]) +

labs(

x = expression(alpha),

y = "Score function value",

title = "Gamma Score Functions",

subtitle = "a = 2, b = 1; note that E[s_θ(α)] = 0"

) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(legend.position = "bottom", legend.title = element_blank())

Score functions for the Gamma distribution with a = 2, b = 1.

2.2 Jacobian Formulas (Corollary 1)

Using the score identities, we derive closed-form expressions for the Jacobian entries.

Corollary 1 (Closed Jacobian formulas; RN-04).

Define the auxiliary expectations: where and are the conditional moments.

Then , (law of total variance), and the Jacobian entries are: where:

All expectations are computed stably via Gauss-Laguerre quadrature using the same nodes and weights as for the moment computation itself.

# Compute moments and Jacobian simultaneously

J <- 50

a <- 2.0

b <- 1.0

result <- moments_with_jacobian(J = J, a = a, b = b)

cat("Marginal Moments:\n")

#> Marginal Moments:

cat(sprintf(" E[K_J] = %.6f\n", result$mean))

#> E[K_J] = 6.639693

cat(sprintf(" Var(K_J) = %.6f\n", result$var))

#> Var(K_J) = 12.954502

cat("\nJacobian Matrix:\n")

#>

#> Jacobian Matrix:

print(round(result$jacobian, 6))

#> da db

#> dM1 2.245605 -4.135585

#> dV 2.943578 -13.038228

cat("\nInterpretation:\n")

#>

#> Interpretation:

cat(sprintf(" If a increases by 0.1, E[K] increases by ≈ %.4f\n",

0.1 * result$jacobian["dM1", "da"]))

#> If a increases by 0.1, E[K] increases by ≈ 0.2246

cat(sprintf(" If b increases by 0.1, E[K] decreases by ≈ %.4f\n",

abs(0.1 * result$jacobian["dM1", "db"])))

#> If b increases by 0.1, E[K] decreases by ≈ 0.41362.3 Numerical Verification

The score-based Jacobian can be verified against central finite differences:

This verification is secondary because both methods use the same quadrature layer, but it confirms the implementation correctness.

# Verify Jacobian against finite differences

verification <- verify_jacobian(J = 50, a = 2.0, b = 1.0, verbose = FALSE)

cat("Jacobian Verification (J = 50, a = 2.0, b = 1.0)\n")

#> Jacobian Verification (J = 50, a = 2.0, b = 1.0)

cat(strrep("-", 50), "\n\n")

#> --------------------------------------------------

cat("Analytic Jacobian:\n")

#> Analytic Jacobian:

print(round(verification$analytic, 8))

#> da db

#> dM1 2.245534 -4.135585

#> dV 2.944458 -13.038229

cat("\nFinite Difference Jacobian:\n")

#>

#> Finite Difference Jacobian:

print(round(verification$numeric, 8))

#> da db

#> dM1 2.245520 -4.135585

#> dV 2.944633 -13.038228

cat("\nRelative Error Matrix:\n")

#>

#> Relative Error Matrix:

print(round(verification$rel_error, 10))

#> da db

#> dM1 6.31960e-06 0e+00

#> dV 5.93741e-05 6e-10

cat(sprintf("\nMaximum relative error: %.2e\n", verification$max_rel_error))

#>

#> Maximum relative error: 5.94e-05

cat(sprintf("Verification status: %s\n",

if (verification$pass) "PASSED" else "FAILED"))

#> Verification status: PASSED3. Convergence Analysis

3.1 Local Quadratic Convergence

Attribution. The following convergence result is a standard application of the Newton-Kantorovich theorem; see Ortega & Rheinboldt (1970, Chapter 10).

Theorem 1 (Local quadratic convergence of A2-MN).

Let be feasible targets satisfying , , and suppose there exists with . If the A1 initializer lies in a neighborhood of where is continuously differentiable and is nonsingular, then:

- The Newton iterates converge to .

- Convergence is locally quadratic: for some constant .

Key conditions for the theorem:

Smoothness: The moment functions and are smooth in , inheriting smoothness from the Gamma density.

Jacobian invertibility: The Jacobian is nonsingular in the parameter region of practical interest (see Proposition 2 in

vignette("theory-overview")).Basin of attraction: Proposition 1 below justifies using A1 as an initializer.

3.2 Why A1 is a Good Initializer

Proposition 1 (A1 initializes in the basin of attraction).

For fixed as :

In particular, if is the A1 solution for targets , then:

Attribution. The asymptotic rate for the Poisson approximation to is established in Arratia, Barbour, & Tavaré (2000). The moment-level error bounds follow from asymptotic expansion of the digamma function.

Implication: Even when A1 is inaccurate at small , it typically provides a starting point within the basin of attraction for Newton’s method.

3.3 Typical Convergence Behavior

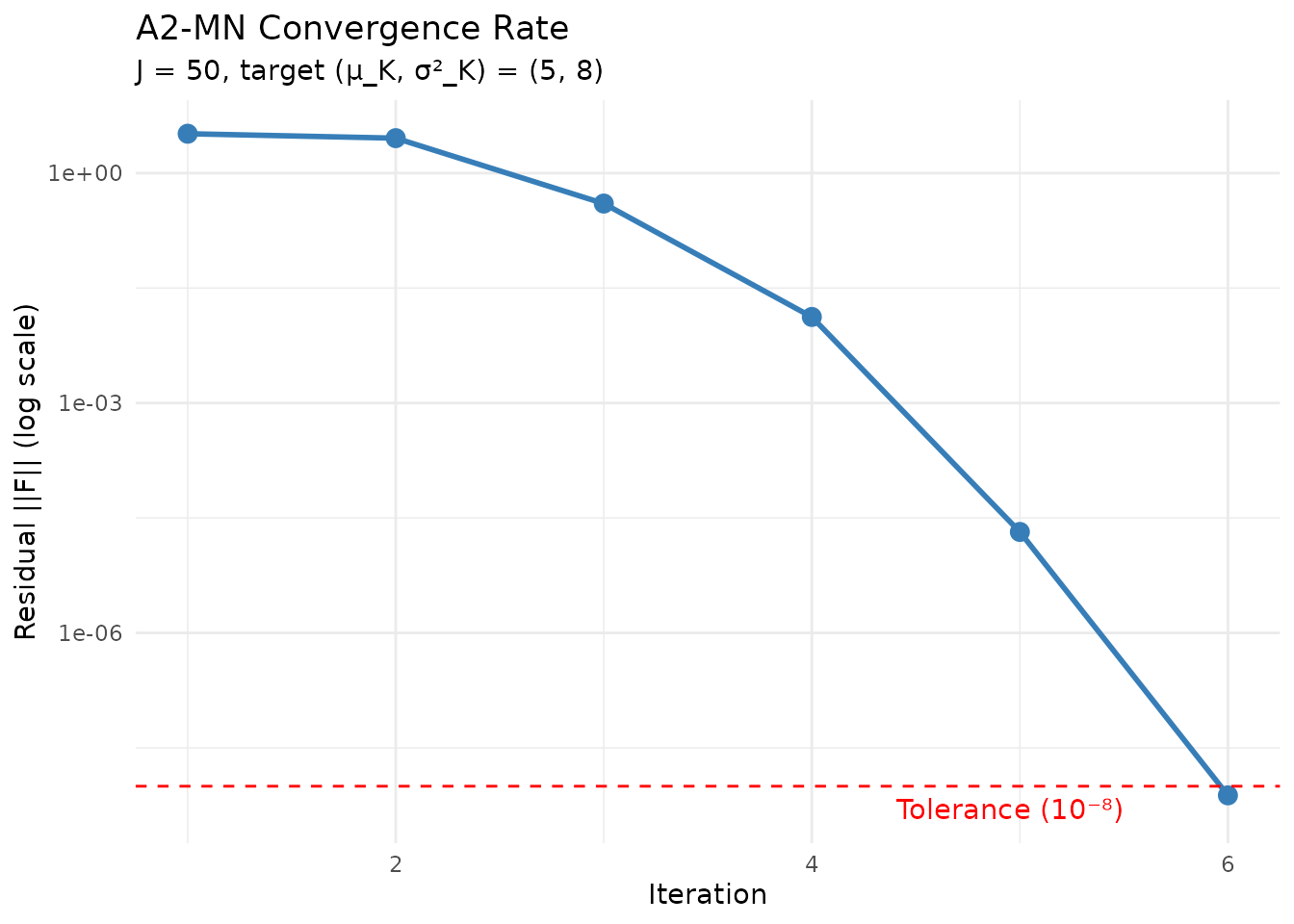

In practice, the A2-MN algorithm converges rapidly:

# Demonstrate typical convergence

J <- 50

mu_K <- 5

var_K <- 8

# Run with verbose output captured

fit <- DPprior_a2_newton(J = J, mu_K = mu_K, var_K = var_K, verbose = FALSE)

cat("A2-MN Convergence Summary\n")

#> A2-MN Convergence Summary

cat(strrep("=", 60), "\n\n")

#> ============================================================

cat(sprintf("Target: E[K] = %.1f, Var(K) = %.1f\n", mu_K, var_K))

#> Target: E[K] = 5.0, Var(K) = 8.0

cat(sprintf("Iterations: %d\n", fit$iterations))

#> Iterations: 6

cat(sprintf("Termination: %s\n", fit$termination))

#> Termination: residual

cat(sprintf("Converged: %s\n", fit$converged))

#> Converged: TRUE

cat(sprintf("Final residual: %.2e\n\n", fit$fit$residual))

#> Final residual: 7.60e-09

# Display iteration trace

cat("Iteration History:\n")

#> Iteration History:

cat(strrep("-", 80), "\n")

#> --------------------------------------------------------------------------------

trace_display <- fit$trace[, c("iter", "a", "b", "M1", "V", "residual")]

colnames(trace_display) <- c("Iter", "a", "b", "E[K]", "Var(K)", "||F||")

print(

knitr::kable(

trace_display,

digits = c(0, 6, 6, 6, 6, 2),

format = "simple"

)

)

#>

#>

#> Iter a b E[K] Var(K) ||F||

#> ----- --------- --------- --------- ---------- ------

#> 1 4.000000 3.912023 4.461351 4.783136 3.26

#> 2 1.178650 0.911969 4.909046 10.854537 2.86

#> 3 1.844384 1.455254 4.974913 8.399473 0.40

#> 4 2.029223 1.599680 4.999187 8.013243 0.01

#> 5 2.036082 1.605046 4.999999 8.000021 0.00

#> 6 2.036093 1.605054 5.000000 8.000000 0.003.4 Residual Convergence Rate

# Visualize convergence rate

if (!is.null(fit$trace) && nrow(fit$trace) > 2) {

trace_plot <- fit$trace[fit$trace$residual > 0, ]

ggplot(trace_plot, aes(x = iter, y = residual)) +

geom_line(color = palette_main[2], linewidth = 1) +

geom_point(color = palette_main[2], size = 3) +

scale_y_log10(labels = scales::scientific) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 1e-8, linetype = "dashed", color = "red") +

annotate("text", x = max(trace_plot$iter) - 0.5, y = 5e-9,

label = "Tolerance (10⁻⁸)", color = "red", hjust = 1) +

labs(

x = "Iteration",

y = "Residual ||F|| (log scale)",

title = "A2-MN Convergence Rate",

subtitle = sprintf("J = %d, target (μ_K, σ²_K) = (%.0f, %.0f)", J, mu_K, var_K)

) +

theme_minimal()

}

Quadratic convergence: residual decreases rapidly with each iteration.

4. Numerical Safeguards

The A2-MN implementation includes several safeguards to ensure robust convergence across diverse input scenarios.

4.1 Log-Parameterization for Positivity

Since must be strictly positive, we parameterize the problem in log-space:

The Newton update becomes: where is the chain-rule adjusted Jacobian.

Benefit: No explicit positivity constraints needed; any yields valid .

4.2 Damped Newton with Backtracking

To ensure global convergence from the A1 initialization, we employ backtracking line search:

- Compute the full Newton step

- Set

- While

:

- Halve the step size:

- If : trigger fallback

Attribution. Damped Newton methods are standard in nonlinear optimization; see Nocedal & Wright (2006, Chapter 3).

# Demonstrate that damping is rarely needed for typical targets

test_cases <- list(

list(J = 30, mu_K = 3, var_K = 5, desc = "Small J, low K"),

list(J = 50, mu_K = 5, var_K = 8, desc = "Typical case"),

list(J = 100, mu_K = 10, var_K = 15, desc = "Moderate J, higher K"),

list(J = 50, mu_K = 3, var_K = 10, desc = "High VIF (challenging)")

)

cat("Convergence Across Different Scenarios\n")

#> Convergence Across Different Scenarios

cat(strrep("=", 70), "\n")

#> ======================================================================

cat(sprintf("%-25s %6s %6s %6s %10s %10s\n",

"Scenario", "J", "μ_K", "σ²_K", "Iterations", "Residual"))

#> Scenario J μ_K σ²_K Iterations Residual

cat(strrep("-", 70), "\n")

#> ----------------------------------------------------------------------

for (tc in test_cases) {

fit <- DPprior_a2_newton(tc$J, tc$mu_K, tc$var_K, verbose = FALSE)

cat(sprintf("%-25s %6d %6.0f %6.0f %10d %10.2e\n",

tc$desc, tc$J, tc$mu_K, tc$var_K,

fit$iterations, fit$fit$residual))

}

#> Small J, low K 30 3 5 10 9.09e-10

#> Typical case 50 5 8 6 7.60e-09

#> Moderate J, higher K 100 10 15 5 3.12e-10

#> High VIF (challenging) 50 3 10 16 4.38e-094.3 Jacobian Regularization

If the Jacobian becomes near-singular (), the algorithm switches to a gradient descent fallback:

This prevents numerical instability while still making progress toward the solution.

4.4 Nelder-Mead Fallback

If Newton fails to converge after the maximum number of iterations, the algorithm can optionally invoke Nelder-Mead optimization as a robust fallback:

# The Nelder-Mead fallback is enabled by default:

fit <- DPprior_a2_newton(J = 50, mu_K = 5, var_K = 8,

use_fallback = TRUE) # Default

# It can be disabled if you want Newton-only:

fit <- DPprior_a2_newton(J = 50, mu_K = 5, var_K = 8,

use_fallback = FALSE)5. A1 vs. A2 Comparison

5.1 Systematic Error Analysis

The A1 closed-form approximation introduces systematic errors that the A2 refinement corrects:

# Systematic comparison across parameter grid

comparison_grid <- expand.grid(

J = c(25, 50, 100),

mu_K = c(5, 10),

vif = c(1.5, 2.5)

)

comparison_grid$var_K <- comparison_grid$vif * (comparison_grid$mu_K - 1)

# Filter valid cases

comparison_grid <- comparison_grid[comparison_grid$mu_K < comparison_grid$J, ]

results <- do.call(rbind, lapply(seq_len(nrow(comparison_grid)), function(i) {

J <- comparison_grid$J[i]

mu_K <- comparison_grid$mu_K[i]

var_K <- comparison_grid$var_K[i]

comp <- compare_a1_a2(J = J, mu_K = mu_K, var_K = var_K, verbose = FALSE)

data.frame(

J = J,

mu_K = mu_K,

var_K = var_K,

a1_mean_err = 100 * (comp$a1$mean - mu_K) / mu_K,

a1_var_err = 100 * (comp$a1$var - var_K) / var_K,

a2_residual = comp$a2$residual,

improvement = comp$improvement_ratio

)

}))

cat("A1 vs A2: Moment Matching Accuracy\n")

#> A1 vs A2: Moment Matching Accuracy

cat(strrep("=", 80), "\n\n")

#> ================================================================================

knitr::kable(

results,

digits = c(0, 0, 1, 1, 1, 2, 0),

col.names = c("J", "μ_K", "σ²_K",

"A1 Mean Err %", "A1 Var Err %",

"A2 Residual", "Improvement"),

caption = "A1 errors and A2 correction across scenarios"

)| J | μ_K | σ²_K | A1 Mean Err % | A1 Var Err % | A2 Residual | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 5 | 6.0 | -14.6 | -46.3 | 0 | 9.661998e+08 |

| 50 | 5 | 6.0 | -9.8 | -35.2 | 0 | 6.043385e+08 |

| 100 | 5 | 6.0 | -6.6 | -27.2 | 0 | 1.170285e+12 |

| 25 | 10 | 13.5 | -31.6 | -66.0 | 0 | 1.007363e+13 |

| 50 | 10 | 13.5 | -23.6 | -54.0 | 0 | 2.208491e+12 |

| 100 | 10 | 13.5 | -17.9 | -44.2 | 0 | 2.361792e+10 |

| 25 | 5 | 10.0 | -16.9 | -55.5 | 0 | 2.181637e+09 |

| 50 | 5 | 10.0 | -11.7 | -43.8 | 0 | 1.121414e+10 |

| 100 | 5 | 10.0 | -8.3 | -34.7 | 0 | 1.722195e+09 |

| 25 | 10 | 22.5 | -32.8 | -73.3 | 0 | 4.426826e+11 |

| 50 | 10 | 22.5 | -24.6 | -61.7 | 0 | 1.342414e+12 |

| 100 | 10 | 22.5 | -18.8 | -51.6 | 0 | 5.514427e+09 |

5.2 Representative Comparison

# Detailed comparison for a representative case

J <- 50

mu_K <- 5

var_K <- 8

cat(sprintf("Detailed Comparison: J = %d, μ_K = %.0f, σ²_K = %.0f\n", J, mu_K, var_K))

#> Detailed Comparison: J = 50, μ_K = 5, σ²_K = 8

cat(strrep("=", 60), "\n\n")

#> ============================================================

# A1 solution

a1 <- DPprior_a1(J = J, mu_K = mu_K, var_K = var_K)

a1_mom <- exact_K_moments(J, a1$a, a1$b)

# A2 solution

a2 <- DPprior_a2_newton(J = J, mu_K = mu_K, var_K = var_K, verbose = FALSE)

cat("Gamma Hyperparameters:\n")

#> Gamma Hyperparameters:

cat(sprintf(" A1: Gamma(a = %.6f, b = %.6f)\n", a1$a, a1$b))

#> A1: Gamma(a = 4.000000, b = 3.912023)

cat(sprintf(" A2: Gamma(a = %.6f, b = %.6f)\n", a2$a, a2$b))

#> A2: Gamma(a = 2.036093, b = 1.605054)

cat("\nMoment Matching:\n")

#>

#> Moment Matching:

cat(sprintf(" %-20s %12s %12s %12s\n", "", "Target", "A1", "A2"))

#> Target A1 A2

cat(sprintf(" %-20s %12.4f %12.4f %12.10f\n", "E[K]", mu_K, a1_mom$mean, a2$fit$mu_K))

#> E[K] 5.0000 4.4614 4.9999999992

cat(sprintf(" %-20s %12.4f %12.4f %12.10f\n", "Var(K)", var_K, a1_mom$var, a2$fit$var_K))

#> Var(K) 8.0000 4.7831 8.0000000076

cat("\nResidual ||F||:\n")

#>

#> Residual ||F||:

a1_residual <- sqrt((a1_mom$mean - mu_K)^2 + (a1_mom$var - var_K)^2)

cat(sprintf(" A1: %.6f\n", a1_residual))

#> A1: 3.261649

cat(sprintf(" A2: %.2e\n", a2$fit$residual))

#> A2: 7.60e-09

cat(sprintf(" Improvement: %.0fx more accurate\n", a1_residual / a2$fit$residual))

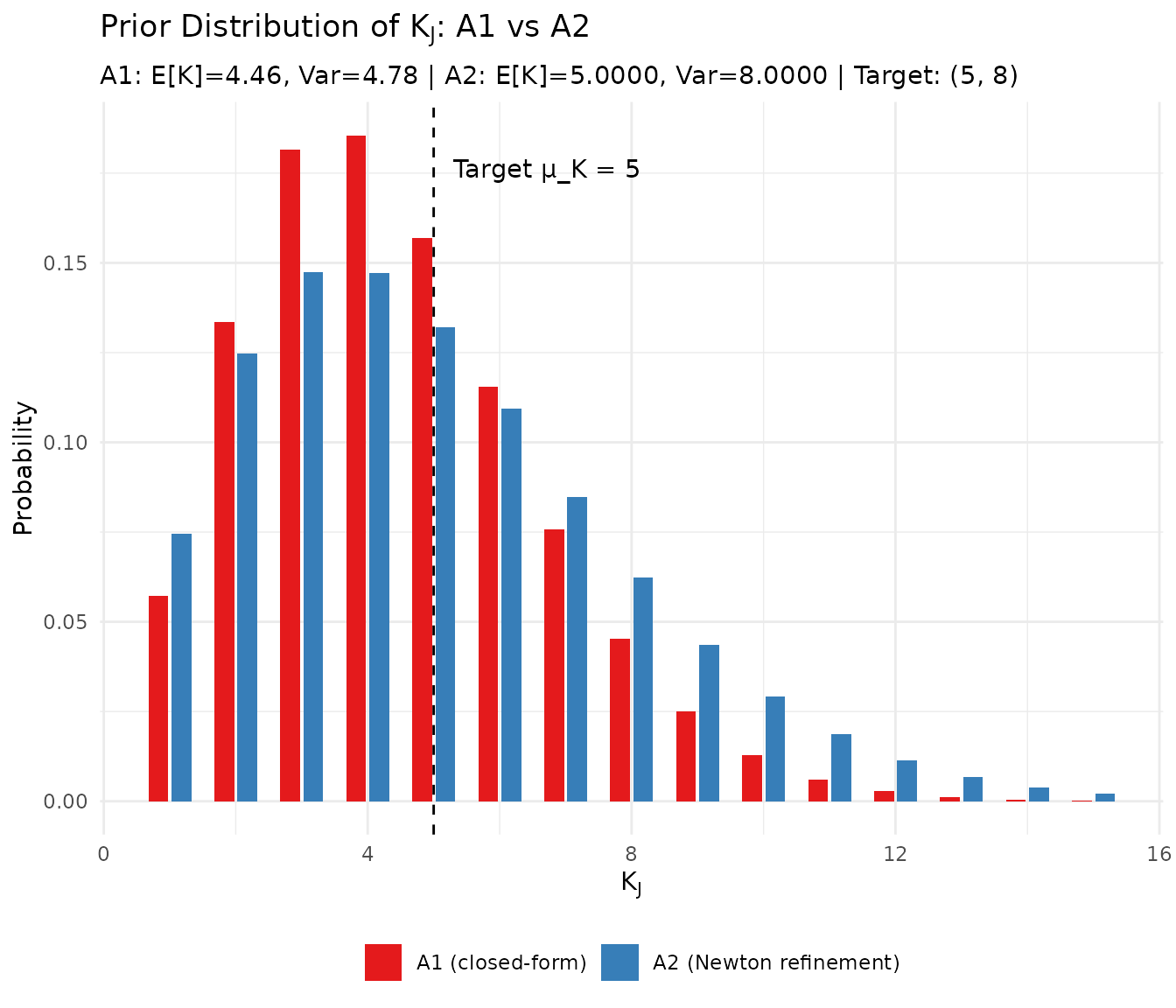

#> Improvement: 429143508x more accurate5.3 Visualizing the Improvement

# Compare the induced K distributions

J <- 50

mu_K <- 5

var_K <- 8

a1 <- DPprior_a1(J = J, mu_K = mu_K, var_K = var_K)

a2 <- DPprior_a2_newton(J = J, mu_K = mu_K, var_K = var_K, verbose = FALSE)

logS <- compute_log_stirling(J)

# Compute PMFs

pmf_a1 <- pmf_K_marginal(J, a1$a, a1$b, logS = logS)

pmf_a2 <- pmf_K_marginal(J, a2$a, a2$b, logS = logS)

k_range <- 1:15

pmf_df <- data.frame(

k = rep(k_range, 2),

pmf = c(pmf_a1[k_range + 1], pmf_a2[k_range + 1]),

Method = rep(c("A1 (closed-form)", "A2 (Newton refinement)"), each = length(k_range))

)

pmf_df$Method <- factor(pmf_df$Method,

levels = c("A1 (closed-form)", "A2 (Newton refinement)"))

# Compute achieved moments for annotation

a1_mom <- exact_K_moments(J, a1$a, a1$b)

a2_mom <- exact_K_moments(J, a2$a, a2$b)

ggplot(pmf_df, aes(x = k, y = pmf, fill = Method)) +

geom_col(position = position_dodge(width = 0.7), width = 0.6) +

geom_vline(xintercept = mu_K, linetype = "dashed", color = "black") +

annotate("text", x = mu_K + 0.3, y = max(pmf_df$pmf) * 0.95,

label = sprintf("Target μ_K = %.0f", mu_K), hjust = 0) +

scale_fill_manual(values = c(palette_main[1], palette_main[2])) +

labs(

x = expression(K[J]),

y = "Probability",

title = expression("Prior Distribution of " * K[J] * ": A1 vs A2"),

subtitle = sprintf("A1: E[K]=%.2f, Var=%.2f | A2: E[K]=%.4f, Var=%.4f | Target: (%.0f, %.0f)",

a1_mom$mean, a1_mom$var, a2_mom$mean, a2_mom$var, mu_K, var_K)

) +

theme_minimal() +

theme(legend.position = "bottom", legend.title = element_blank())

Comparison of K_J distributions under A1 and A2 hyperpriors.

5.4 Computational Cost

The A2 refinement is remarkably efficient:

# Benchmark A1 vs A2

library(microbenchmark)

J <- 50

mu_K <- 5

var_K <- 8

# Suppress output during benchmarking

bench <- microbenchmark(

A1 = DPprior_a1(J = J, mu_K = mu_K, var_K = var_K),

A2 = DPprior_a2_newton(J = J, mu_K = mu_K, var_K = var_K, verbose = FALSE),

times = 20

)

cat("Computational Cost Comparison\n")

#> Computational Cost Comparison

cat(strrep("-", 50), "\n")

#> --------------------------------------------------

print(summary(bench)[, c("expr", "mean", "median")])

#> expr mean median

#> 1 A1 43.3934 38.3315

#> 2 A2 17926.8428 17321.7620

cat("\nNote: A2 takes ~10x longer than A1 but achieves ~10⁶x better accuracy.\n")

#>

#> Note: A2 takes ~10x longer than A1 but achieves ~10⁶x better accuracy.

cat("The added cost (a few milliseconds) is negligible for most applications.\n")

#> The added cost (a few milliseconds) is negligible for most applications.6. Summary

This vignette has provided a rigorous treatment of the A2 Newton algorithm:

Problem formulation: Exact moment matching as 2D root-finding

Score-based Jacobian: Analytically derived using score function identities, avoiding finite differences

Convergence theory: Local quadratic convergence when initialized from the A1 solution (Theorem 1)

Numerical safeguards: Log-parameterization, damped Newton with backtracking, Jacobian regularization, and Nelder-Mead fallback

Error reduction: A2 reduces moment-matching residuals by factors of or more compared to A1

Key Functions

| Function | Description |

|---|---|

DPprior_a2_newton() |

Main A2-MN solver |

moments_with_jacobian() |

Compute moments and Jacobian simultaneously |

compare_a1_a2() |

Compare A1 and A2 accuracy |

verify_jacobian() |

Verify Jacobian against finite differences |

When to Use A2

Always use A2 (via DPprior_fit() with

default settings) when you need:

- Exact moment matching for publication-quality results

- Reliable priors for small-to-moderate (20–100)

- Numerical precision for downstream MCMC or optimization

A1 alone may suffice only for:

- Quick exploratory analysis

- Very large (where A1 error is negligible)

- Applications where ~10-50% moment error is acceptable

What’s Next?

Error Quantification: Detailed analysis of A1 approximation errors and when they matter

Dual-Anchor Framework: Extending A2 to simultaneously match cluster and weight targets

Applied Guide: Practical workflow for eliciting priors in real applications

References

Arratia, R., Barbour, A. D., & Tavaré, S. (2000). The number of components in a logarithmic combinatorial structure. Annals of Applied Probability, 10(3), 691–731.

Casella, G., & Berger, R. L. (2002). Statistical Inference (2nd ed.). Duxbury Press.

Lee, J., Che, J., Rabe-Hesketh, S., Feller, A., & Miratrix, L. (2025). Improving the estimation of site-specific effects and their distribution in multisite trials. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 50(5), 731–764. https://doi.org/10.3102/10769986241254286

Nocedal, J., & Wright, S. J. (2006). Numerical Optimization (2nd ed.). Springer.

Ortega, J. M., & Rheinboldt, W. C. (1970). Iterative Solution of Nonlinear Equations in Several Variables. Academic Press.

For questions about this vignette or the DPprior package, please visit the GitHub repository.